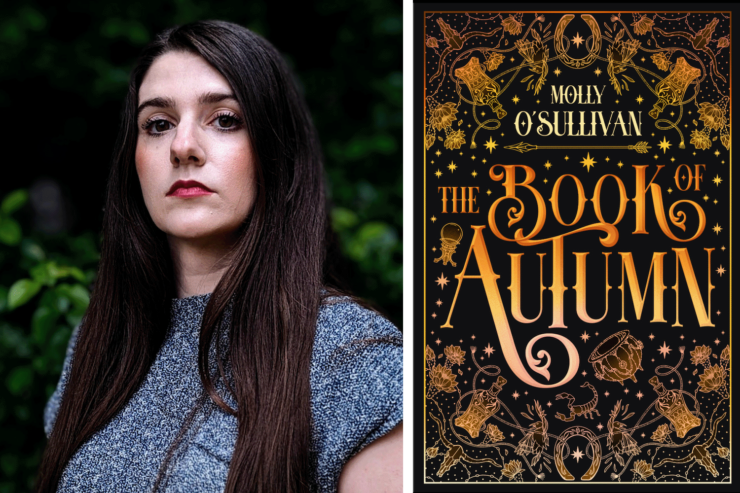

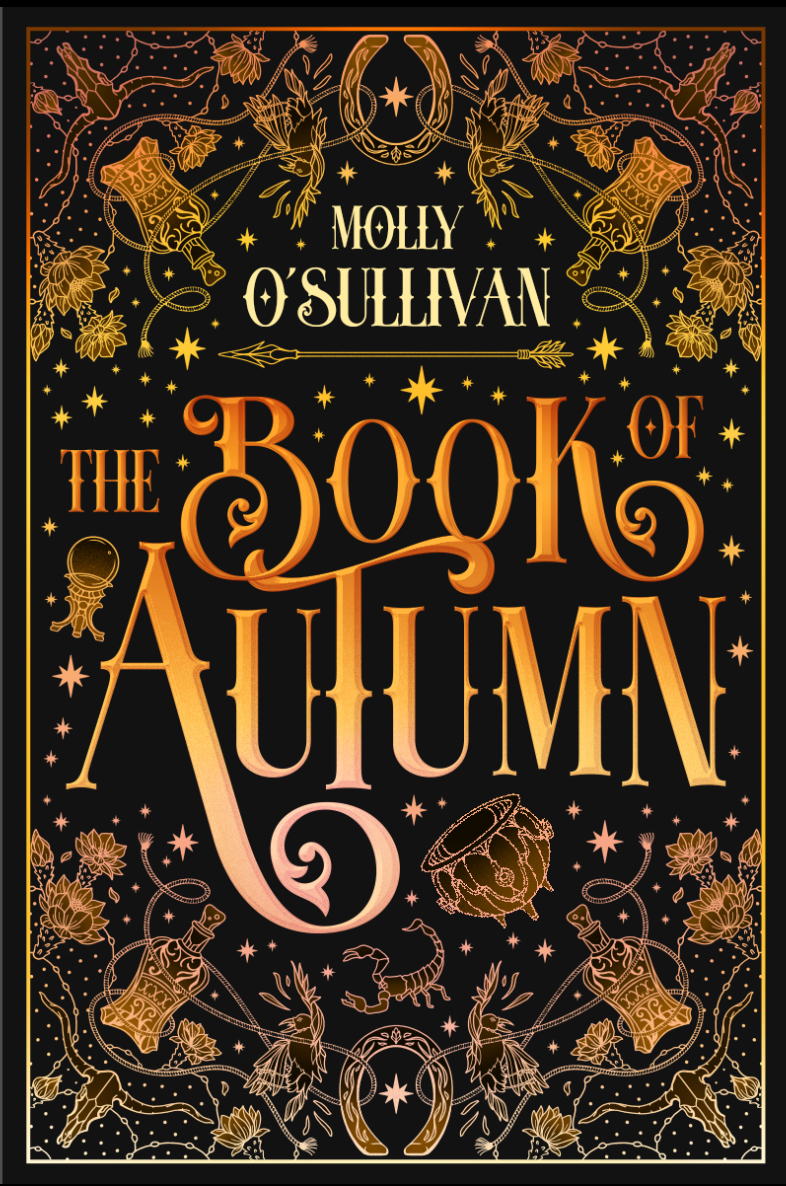

We’re thrilled to share the cover and preview an excerpt from Molly O’Sullivan’s debut novel The Book of Autumn—available October 28, 2025 from Kensington Publishing.

Max’s Magic was sunny and a little rough like saddle leather; it felt warm like summer rain on the back of your neck. Whereas whenever I did Magic, I always ended up sopping wet and in the dark.

In a world where magic is drawn from a person’s three most treasured objects, Cella Gibbons would give anything for her powers to be bound by objects alone. Instead, she’s one half of a dimidium, a rare kind of magician who is bound to another person and must be near them to access her magic.

The catch? Her dimidium is Max Middlemore. And they’ve burned each other before. Preferring a life without power to her painful past with Max, Cella leaves behind her studies at a magical university to forge a path of her own—alone. But when the headmaster calls both Cella and Max back to investigate the possession of a young student, Cella is forced to confront the bond she’s spent years trying to escape.

With someone casting malevolent spells on students, something far more powerful threatens Cella and Max than their own friction…

Perfect for fans of Leigh Bardugo’s Ninth House and Rebecca Ross’s Divine Rivals, The Book of Autumn is a spellbinding debut about second chances, the cost of ambition, and what we’re willing to do to our souls for love.

Molly O’Sullivan is a cybersecurity engineer turned speculative fiction writer with a deep love for the natural world, tea, and for characters who, despite everything, still manage to hope. Originally from South Carolina, she has lived all over the country but now resides outside Seattle. Visit her online.

Buy the Book

The Book of Autumn

Chapter One

Some places never let go of you. They slip inside your pores, cling to your neck like a leech. And though you fight like hell to break loose, there’s no stopping it. The place is part of you now. It’s in your blood.

Seinford and Brown College was in my blood. That had to be it. Had to be how, despite a whole host of circulating night- mares over the last five years, it still had me here. Driving down this road, slowing as I reached the sign welcoming me to Marble County, New Mexico, which was nearly rusted of its hinges. Beside it was a spray-painted one that read jesus heals.

I sighed and patted the steering wheel of the old pickup. “I dunno, Jesus, that might be a bigger job than you bargained for.”

My husky, Bear, barked in the seat beside me and stuck his head out the window.

Marble County, New Mexico, sat between the southwestern tip of Colorado’s border and the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Everything in the county was parched. Mesas towered over rust-red earth covered in creosote bushes and sagebrush. Stray dogs nosed the dirt for something to chew on, finding nothing but bits of tire from the surrounding farms.

In the distance, a wooden sign flapped against the gate of Ludlow Ranch.

I swallowed, talking aloud to keep my thoughts from racing. “This is going to be fine. One job, enough to set us up for a while, then we can move on. For real this time.” Bear howled with excitement at a cracker he found wedged in the seat, flipping it from side to side to lick of the salt.

The conversation stuck like a splinter in the back of my mind. I hadn’t even jumped when I saw Max standing outside the café two days ago, cowboy hat tucked low over his face, only too proud of himself for finding me again.

I blew out my cheeks, shoulders slumping. “I guess I should just give up on you people ever leaving me alone.”

“You’re a Magician, sweetheart,” he said, grinning and leaning against a wall. “This shit you can do isn’t going to just go away. And you’re too damn talented to drop of the face of the earth. Besides”—he tapped the envelope he was holding—“I think you’re going to want to see this one for yourself.”

I glanced down at the letter, now folded in the seat beside me. “Bear!” I wiped it with my sleeve, trying to save it from Bear’s drool. It had been a long drive from Portland, and we were both looking a little worse for the wear. There wasn’t much to it. Only:

Cella,

There’s been an incident at school. I need your help and knowledge of Object Theory in the investigation. I can’t include many details here; it’s something you’d best see for yourself. Please come. I promise I’ll make it worth the journey.

Dr. Thea H. Robetresse

(P.S. Sorry about the choice of courier—Max insisted.)

Object Theory1 said everyone had a comfort object. A warm blanket or spot on the couch, a favorite book, a ham- mock under an old, creaking tree. Once upon a time, I was an expert in the theory, a budding anthropologist who loved her work and pushed hard for discoveries in the field. Now one of my own objects, the leather cord from an old journal, was wrapped so tight around my finger it could’ve snapped the bone in two. I’d jumped from job to job after leaving New Mexico, from working in a museum to a retail job to where Max ultimately found me, working at a coffee shop on the outskirts of Portland. Didn’t really matter what I did, as long as there was no Magic involved.

But no matter how far I went, Magic always found me. It leaked out of my fingers, flooding the exhibits and scaring the shit out of the museum’s visitors, or fried the cash register, or broke the espresso machine at work.

I couldn’t seem to escape, and so now here I was, trudging back to this damn place with my very last bit of gas and a grand total of thirteen dollars in the bank, and holding onto that leather cord for dear life. I swore to myself this was the last time, the very last time I’d be back. I just needed enough to get myself on my feet again, to repair the truck and cover a month’s rent or so, and then I would vanish for good, so far away they wouldn’t be able to bother me again. Far enough away that I could start fresh, that Magic wouldn’t get me fired from every job I had—far enough that even the nightmares couldn’t reach.

My truck rolled under the sign for Ludlow Ranch. Rust-colored dust kicked up behind us, coating a bull skull. What was once Ludlow Cattle Ranch was now Seinford and Brown College of Agriculture—though it was really Seinford and Brown College of the Three Arts.

“It is your alma mater,” Max had said that day, so quietly I nearly didn’t hear him, “and you’re still on the council. You must care at least a little about what happens there. We wouldn’t have asked if it wasn’t important. A student is unwell.”

“But why me?” I asked, aware of how close my pitch came to whining. I cursed the day I agreed to be on Seinford and Brown’s Advisory Council. Apparently, they all considered my appointment a life term, despite the fact that I hadn’t been to one of their stupid meetings in years. “I’m no doctor. My objects have nothing to do with medical aid. There’s little I can do for a sick student.”

“Not that kind of unwell,” he’d said quietly, and a prickle of unease slid down my shoulders.

Now the bump of my truck along the dirt road snapped me back to present. Bear barked at a group of students walking to class.

I gnawed on my lip, shoving the bangs out of my face. They’d ballooned in the heat, and I was rapidly giving up hope of taming “the Wall,” the lovely nickname my mass of brown hair had been given in middle school. I cast a glance around me. “Yep, this place is definitely cursed.”

There it was, Ludlow House, the sprawling adobe ranch house at the front of Ludlow Ranch. Built in 1883, the house was once home to the cattleman William Jameson Ludlow, his wife, Josephine, and their twelve children. After he went mad and pitched himself into the canyon, the house passed through a smattering of hands. None outside the family held it for longer than a year. There were complaints that the hallways stretched and twisted in on themselves, that in the low light, the red clay tile floors looked bloody. The ranch was more or less abandoned until the early 2000s, when Thea Robetresse bought it for a fraction of what it was worth. On its sprawling acres, she built a school.

Though Ludlow House wasn’t the largest of the academic halls, the other buildings could do little but linger in its shadow. Its adobe walls blended into the red hills and mesas at its back as though it had been painted there. Iron lanterns and Spanish doors gave it a darkness that stood in defiance of the sun that baked the acres beyond it.

Behind it stood the rest of campus: three dormitories, the auditorium, the library, and the academic buildings. Greek fraternities and sororities were housed in smaller adobe buildings clustered near the fence’s edge at the far side of campus. Over to the left was the main parking lot, on the ridge of a steep canyon.

They didn’t have any cloaking enchantments over the college—too expensive—just relied on good old-fashioned geography. Sixty acres in the middle of a desert that reached 125 degrees before noon was ample-enough deterrent.2

Behind the Granary, the massive barn converted into a cafe- teria, was the infirmary, where I was to report. A squat, pueblo- style cottage, the infirmary was one of the many dwellings that had belonged to ranch hands who used to work the property. This one was now home to the school’s nurse, Maritza.

The cottage’s door swung open as my truck sputtered to a stop.

I snuck one last glance in the mirror. Peeking out beneath the Wall were two rapidly blinking brown eyes. Bear was scarfing down his cracker as fast as possible.

I took a deep breath. “Everything is going to be fine.”

As I stepped out of the truck, fingers clenched around my leather cord, I couldn’t help but wonder how this place had pulled me back, yet again, nearly five years since I’d abandoned my PhD program. The sensation was so familiar, like falling into a deep, dark well.

- A fundamental theory in Esoteric Psychology and a founding theory of the Three Arts. First originated in 1952; expanded upon in 2014. See also M. P. Gibbons, “Object Study: Advantages and Disadvantages of Base Materials in the Conveyance of Magic,” New Magic Quarterly, Issue 427.

- As a rule, we Magicians did try to hide and downplay the existence of Magic. We knew it was best not to draw attention to ourselves, but it wasn’t easy keeping too many secrets in the age of the internet. It turned out not to matter much. If you went around screaming you could do Magic, people usually just gave you a polite smile and walked away quickly.

Excerpted from The Book of Autumn, copyright © 2025 by Molly O’Sullivan